MM Curator summary

The article below has been highlighted and summarized by our research team. It is provided here for member convenience as part of our Curator service.

[MM Curator Summary]: Pharma will argue that asking them to explain how the calculate their prices to CMS is stealing their private property under the 5th amendment.

Clipped from: https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/medicaid-drug-proposal-sets-up-likely-constitutional-challenge

Provisions in a proposed HHS policy aimed at driving down drug costs to the Medicaid program overstep the agency’s authority and are likely to face a constitutional challenge, attorneys say.

The proposed rule (RIN: 0938-AU28), issued in May, aims to prevent the misclassification of drugs, particularly when brand-name drugs are inaccurately labeled as generic, which can result in lower rebate payments for states.

Lawyers representing drugmakers say the proposal would rewrite the rules of engagement for drug companies looking to do business with the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, a partnership that allows drug makers access to the nation’s 94 million Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries in exchange for offering Medicaid agencies the lowest possible price for prescription drugs.

They pointed to a move by the department’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to clarify ambiguous terminology that allowed drugmakers to avoid paying higher rebates to Medicaid. They also criticized a requirement that manufacturers of between three and 10 of the costliest drugs in the drug rebate program complete surveys detailing proprietary information such as production expenses, research costs, and international pricing.

The agency’s tightening grip on drug prices comes as costs associated with covering expensive specialty drugs like gene and cell therapies continue to spiral.

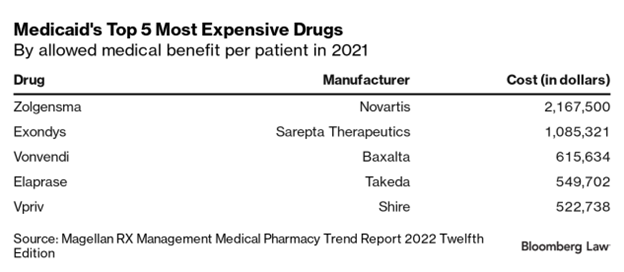

A report from the Magellan Rx Management, one of the nation’s largest Medicaid pharmacy benefit managers, found six drugs with an average cost per patient in 2021 of over $100,000. Two drugs, Novartis’ Zolgensma and Sarepta Therapeutics’ Exondys, used to treat muscular dystrophy, topped out at over $1 million per patient.

An earlier report by the Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General said that, without greater government oversight to control spending, the per-enrollee rates that state Medicaid agencies must pay to managed care organizations would continue to rise dramatically as more and more high-cost drugs enter the market.

The proposed rule’s reporting requirement would try to rectify this by requiring manufacturers to offer medicines priced within the top 5% to negotiate significant rebates either directly with CMS or with 50% of state Medicaid agencies.

Those that don’t would have to send CMS details of their proprietary pricing information. Manufacturers that fail to comply with the information requests within 90 days would be imposed fines of up to $100,000.

Takings Clause

William A. Sarraille, attorney at Sidley Austin LLP, a law firm that represents pharmaceutical companies including Pfizer and AstraZeneca, said that the CMS’s new drug price reporting rules violate legal protections for trade secrets. He also said mandating that companies share financially sensitive proprietary data breaches the takings clause of the Fifth Amendment, which bars taking private property for public use without just compensation.

“What the [drug companies] are saying is that since the statute doesn’t authorize the scope of the survey information that’s being mandated—and there’s concern regarding trade secret information being disclosed to the public and therefore the value of the trade secret being undermined—that this amounts to a regulatory taking without just compensation,” Sarraille said.

Edwin Park, a research professor at the Georgetown Center for Children and Families, pushed back against claims that the CMS lacks authority to require drugmaker surveys. Park said Section 1927(b)(3)(B) of the Social Security Act has allowed the CMS to survey manufacturers since the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program began in 1991. However, the CMS has refrained from exercising this power until now.

The act permits the CMS to “survey wholesalers and manufacturers that directly distribute their covered outpatient drugs, when necessary, to verify manufacturer prices,” Park said.

The takings clause argument echoes that made by several drugmakers challenging the Medicare drug pricing provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act. Merck & Co. and Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. argue in their lawsuits that patented drugs are “protected from uncompensated takings” under the takings clause. Johnson & Johnson and Astellas Pharma Inc. also cited the takings clause in their litigation against the IRA.

Top courts have stuck down such claims in challenges to other federal programs, including the Affordable Care Act, the No Surprises Act, and the 340B drug pricing program.

Park argues that the CMS survey, while not ideal for drug companies, would give state Medicaid agencies the information they need to negotiate fairer drug prices with manufacturers. That’s a better option than the alternative, where states looking to lower spending on drugs could implement a closed Medicaid formulary that would cover just one drug per class, excluding high-cost drugs based on price alone, he said.

‘Best Price’ Debate

Another contentious aspect of the proposed rule is the CMS’s move to redefine and clarify established terms within the Medicaid statute, lawyers say.

According to Sarraille, a provision within the proposed rule would fundamentally alter how drug manufacturers calculate Medicaid rebates by modifying the regulatory definition of “best price” to require manufacturers to stack, or aggregate, all discounts and rebates across the pharmaceutical supply chain when determining the lowest net price for a drug.

“Best price has historically been understood [by drugmakers] as the best price offered to any one included purchaser within the statute. So if there’s a 40% discount to a particular managed care entity, that would be one potential best price point. And then if there’s a 10% discount to a retail pharmacy chain that would be another potential best price point,” Sarraille said.

“What CMS is proposing to do is not to consider those different potential price points, but to say, if the pill goes through the retail pharmacy, and is ultimately paid by the managed care entity, then the best price is not the higher of 40 or 10% off. It’s both 40% plus 10% off,” he said.

Legal challenges by drug manufacturers argue the existing regulations are vague on whether stacking is required.

The US Supreme Court recently ordered the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit to rehear an appeal of a lower court’s decision in U.S. ex rel. Sheldon v. Allergan. The lower court dismissed a complaint alleging the drugmaker violated the False Claims Act because it chose not to stack discounts provided to separate entities.

The district court had ruled in favor of the manufacturer, finding the company’s interpretation against stacking was “objectively reasonable” since CMS regulations hadn’t explicitly required it.

To assuage any doubt over the agency’s intentions, the CMS proposed rule added explicit language to its regulatory statement that “manufacturer[s] must adjust the best price for a covered outpatient drug for a rebate period if cumulative discounts, rebates or other arrangements to best price eligible entities subsequently adjust the price available from the manufacturer for the drug.”

Need for Negotiation

Peter Pitts, president and co-founder of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest and a former associate commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration under President George W. Bush, said it’s going to take negotiation on both sides in order to avoid litigation.

Pitts was critical of the CMS’s approach, saying it wasn’t “collegial.” Of the proposed rule, he said, “all they change is CMS’s ability to—not clarify the rules, but change the rules as they see fit.”

“The problem right now is that both sides aren’t negotiating in good faith,” he said.