MM Curator summary

New information suggests that the former Medicaid director helped the losing plan lobby lawmakers to require the bids be thrown out.

The article below has been highlighted and summarized by our research team. It is provided here for member convenience as part of our Curator service.

Disappointed bidder seeking a do-over

The Republican leadership of the Ohio Senate is attempting to give an Ohio-based Medicaid managed-care company a do-over after it failed badly in a competitive process to keep its business with the state.

Critics say the do-over — which was apparently lobbied for by the previous Medicaid director — would at least delay a series of reforms to a Medicaid system that has been vulnerable to huge rip-offs related to prescription drug purchases. It also threatens a new program that would coordinate care for up to 60,000 kids with complex behavioral needs, critics add.

Perhaps worst of all, said one opponent, using legislation to possibly restore a contract to a business that lost it through competitive bidding sets a terrible example for all future failed bidders.

“Regardless of the rationale, I have tremendous concern that unravelling the Medicaid managed-care procurement after-the-fact undermines the whole intent of the competitive bidding process, which is a necessary accountability mechanism in the system,” said Antonio Ciaccia, who helped lead the drive to reform the way Ohio spends billions annually on prescription drugs. “It would send a signal to the entire insurer marketplace that if you underperform and lose out, all you have to do is lobby and litigate your way back into the winner’s circle.”

Whether the do-over will happen will partly be decided in the coming days as conferees from the Ohio House and Senate hash out a compromise budget that would go to Gov. Mike DeWine for his signature, or veto. If DeWine is forced to make such a decision, it promises to be politically dicey for him.

Claims of bias

The care company that would benefit from the do-over, Paramount Advantage, says it’s the victim of a flawed process that stands to cost Northwest Ohio 600 jobs.

“Paramount maintains that the Ohio Department of Medicaid’s managed care organization… procurement process was systemically flawed and unfair,” Tausha Moore, its director of public relations, said in an email Wednesday. “Out-of-state, for-profit, multi-billion-dollar Fortune 500 companies appear to have been favored over mission-driven, not-for-profit managed care organizations headquartered in Ohio, including those that have received some of the highest quality scores as Medicaid managed care providers.”

Paramount Advantage is a subsidiary of Toledo-based ProMedica, a health care system operating in Northwest Ohio and Southeast Michigan. And while it and many other health care systems are 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations, they’re quite profitable for their top employees.

ProMedica’s 2018 tax filings show that it had six employees making more than $1 million that year and 18 others earning more than $500,000.

Paramount is a longtime Ohio Medicaid managed-care organization, meaning that it creates networks of providers such as doctors for its Medicaid clients, handles reimbursements and works to create savings because it receives a fixed amount each year for each client it serves. But during its tenure, the Medicaid managed-care system has faced problems.

In 2016, Paramount and the other four managed-care companies serving Ohio Medicaid came under scrutiny over the conduct of companies they hired to handle pharmacy benefits. Pharmacists around the state complained that those companies, known as pharmacy benefit managers, used a non-transparent system to often reimburse them below their cost, billed companies such as Paramount top dollar and then pocketed the difference.

An analysis of 2017 transactions showed that for the cheapest class of drugs alone, pharmacy benefit managers CVS Caremark and OptumRx billed the state almost a quarter billion dollars more than they reimbursed pharmacists.

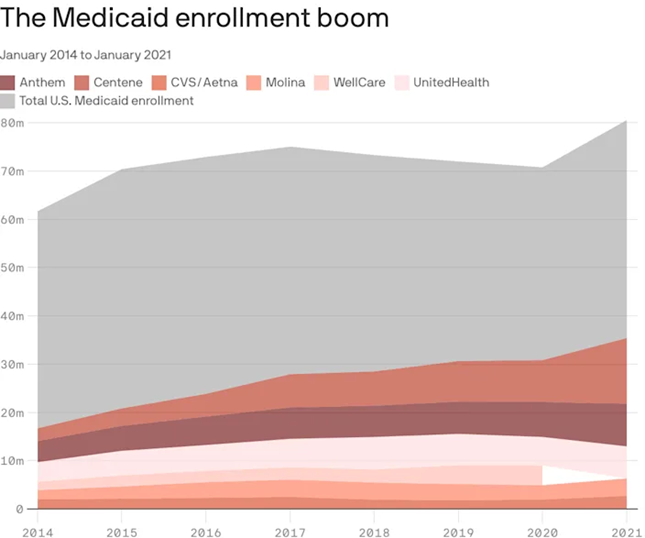

More recently, Centene, owner of another managed-care plan, this month agreed to pay $88 million after Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost accused it of a number of bad acts, including using a chain of pharmacy benefit managers in a scheme that amounted to double billing. The company has set aside more than $1 billion to settle claims of wrongdoing with other states’ departments of Medicaid.

Attempted reforms

DeWine’s Medicaid Director, Maureen Corcoran, and the legislature are implementing sweeping changes intended to address those and other problems.

One is intended to shed more light on drug transactions by hiring a single pharmacy benefit manager to work directly for the state, instead of behind the curtain of managed-care providers such as Paramount and Centene’s Buckeye Health.

The change seems to promise savings for taxpayers. Centene CFO Drew Asher last week described such carveouts as a “headwind” as he explained to analysts the company’s plans to grow profits.

Another reform is a broader redesign of the Medicaid managed-care system, with would-be contractors required to submit bids explaining how they would implement the new vision. And a big part of that vision is the implementation of the OhioRISE program.

A major DeWine initiative, the program is intended to coordinate services for kids with “significant mental/behavioral health and substance use disorders, in addition to medically complex illnesses,” the program’s description says.

Currently, up to 60,000 such children are receiving care from various agencies. Advocates say a lack of coordination creates some excruciating gaps.

“OhioRISE is the state’s answer to the ongoing, multi-decade issue of custody relinquishment,” said Loren Anthes, Treuhaft chair in health planning at the Cleveland-based Center for Community Solutions. “The idea is that adolescents that are involved in multiple systems — often who have developmental delays, and who are engaged with the foster-care system or Medicaid or the corrections system or all of the above — couldn’t get access to basic services and kept getting hospitalized over and over again.

“In order for them to receive some essential services, many times parents would have to hand their children over to the county government in order to get those benefits and those parents were no longer the guardians,” he said.

Anthes explained that not nearly all of the children who would be helped by OhioRISE face being handed over by desperate parents to county health authorities. But the program is aimed at keeping all from that dire situation, he said.

“You don’t want to wait for them all to be hospitalized; you don’t want to wait until the moment of crisis,” he said. “But things aren’t very coordinated right now.”

Sen. Theresa Gavarone, R-Bowling Green. Official photo.

However, measures inserted into the budget at the behest of Senate President Matt Huffman, R-Lima, and Sen. Theresa Gavarone, R-Bowling Green, could keep OhioRISE from getting off the ground next year as planned.

Anthes said the Medicaid redesign depends on multiple things occurring simultaneously. They include hiring managed-care providers — including the single pharmacy benefit manager, which would itself function as a managed-care provider. Those entities would then work together to help launch OhioRISE, he said.

“All of these things are premised on moving forward at the same time,” Anthes said, adding that if they don’t, everything will fall apart.

Paramount spokeswoman Moore said those concerns are unfounded.

“Whether stemming from misdirected concern or political motivation, that assumption is just not true,” she said. “An amendment (to the budget) specifically clarified that the changes in the MCO procurement process would not apply to OhioRISE.

Paramount lost by a lot in its unsuccessful bid to manage Medicaid care for two regions of Ohio. It received roughly half the score of the lowest of six companies that were selected to provide managed care starting next year.

The Toledo Blade last week reported that one knock against the Paramount proposal was that it didn’t adequately explain what Paramount would do to facilitate the launch of OhioRISE. For example, the Paramount bid only mentioned the program 17 times, while the highest-scored bid mentioned it 94 times.

Paramount President Lori Johnston seemed dismissive when asked about that critique.

“I guess in hindsight we should have thrown that buzzword out a few times,” she told The Blade. “I don’t think the number of times we used OhioRISE should be indicative of our approach and understanding of that plan. We support the program and are very committed to seeing the program is successful with that population.”

Political implications

A spokesman for Senate Republicans didn’t respond to questions for this story. But they apparently inserted language mandating a new bid process partially at the urging of Barbara Sears, who was Medicaid director under DeWine’s predecessor, John Kasich. Corcoran, the current Medicaid director, early last year said she inherited a mess from Sears when she took the helm in early 2019.

Now a principal with the lobbying firm Strategic Health Care, Sears registered this year to lobby on behalf of Paramount owner ProMedica on the budget and on the Medicaid managed care procurement.

Her participation is notable for a few reasons.

First, she’s in the pay a client that had a mammoth contract with Ohio Medicaid while she was running the agency. And if, as critics say, the Senate budget measure delays reforms it could mean Sears worked to delay fixes to problems that developed on her watch as Medicaid director.

She didn’t respond to questions sent to an email address listed on her lobbying-disclosure forms.

If House and Senate conferees keep the requirement to rebid Medicaid managed-care business in the budget, they’ll be placing DeWine in a politically painful position.

He’s already under attack from his right for taking measures against the coronavirus pandemic that some claim were dictatorial.

Now he might have to decide between two of his most important initiatives or issuing a veto that Paramount says would cost Northwest Ohio 600 jobs. And DeWine might have to make that decision with a contested primary less than a year away.

A DeWine spokesman didn’t respond to questions about the matter on Tuesday.

Clipped from: https://ohiocapitaljournal.com/2021/06/24/proposed-budget-changes-said-to-threaten-medicaid-reforms/