MM Curator summary

A new expose shows how hospitals diverted money meant for nursing homes in a widespread, multi-year scandal.

The article below has been highlighted and summarized by our research team. It is provided here for member convenience as part of our Curator service.

A tip about Indiana’s largest nursing home system leads an investigative team to expose how public hospital officials in Indiana exploited the Medicaid program’s lax oversight.

Annually, the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy awards the Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting to a stellar investigative report that has had a direct impact on government, politics and policy at the national, state or local levels. Six reporting teams were chosen as finalists for the 2021 prize, which carries a $10,000 award for finalists and $25,000 for the winner. The Journalist’s Resource is interviewing many of the finalists to offer a behind-the-scenes look at the processes, tools and legwork it takes to create an important piece of investigative journalism. The entry discussed here, “Careless,” was published in the Indianopolis Star. The Journalist’s Resource is a project of the Shorenstein Center, but was not involved in judging the Goldsmith Prize. The winner of the $25,000 will be announced on April 13.

What started as a tip about Indiana’s largest nursing home system led an investigative team at the Indianapolis Star to expose how public hospital officials in Indiana exploited the Medicaid program’s lax oversight to take billions of dollars in federal money meant to go to nursing homes and divert them to build shiny new hospital facilities. In some cases, hospital executives took home large compensation packages while diverting the money.

The journalists revealed that even though Indiana raked in more supplemental Medicaid funds for nursing homes than almost any other state, its nursing homes ranked among the worst in the nation. Most were understaffed, a problem that was exacerbated by the pandemic and led to hundreds of deaths that potentially could have been prevented, the reporters learned.

What the county hospitals have been doing is not illegal. They’ve been taking advantage of a regulatory loophole in the Medicaid program. But the scheme has been marred with scandals and fraud. In 2016, federal officials prosecuted five people and recovered $15.5 million in taxpayer dollars in scandals involving the nursing homes. But there was more. With their in-depth investigative series, “Careless,” the reporters gained the trust of a source who shared a secret, 277-page report that claimed 20 more people were involved in a number of schemes to defraud Indiana’s nursing home system of at least $35 million.

As a result of the stories, Indiana’s largest public hospital system, the Health & Hospital Corp. of Marion County, commissioned an outside review of its nursing home operations in May. In August, the hospital system’s long-time leader was forced to resign by the board. City officials, who oversee the hospital corporation’s budget, held a special hearing and budgeted additional tens of millions for its nursing home operations. At the state level, Gov. Eric Holcomb said in December that his office was working on reforms to the state’s elder care that could tie Medicaid payments to nursing home quality, according to the newspaper.

“What’s not being discussed is increasing Indiana’s minimum staffing ratios,” says Tony Cook, an investigative reporter at the Indianapolis Star, who received the initial tip in 2019.

His editor, Steve Berta, known for looking at the bigger picture, suggested taking a close look at where the nursing home money was coming from. Cook teamed up with two colleagues, veteran investigative reporter Tim Evans, who was inducted to Indiana Journalism Hall of Fame last year, and data reporter Emily Hopkins. They set out to follow the money trail.

Following the money

The nursing home industry is complicated and often secretive. The IndyStar investigative team, which faced pushback from local hospitals, had a steep learning curve. But that didn’t deter them from pursuing the story.

“There are layers and layers and it did take a while to really understand how it all worked,” Cook says. “The way we did it was just by trying to understand how the money flowed.”

Medicaid is a state and federal public health program for low-income individuals, including seniors who need nursing home care.

The IndyStar team used an annual report compiled by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, or MACPAC, to understand what types of Medicaid funds their state received and how it compared with other states.

“The first step is to understand whether or not your state receives these types of funds,” says Hopkins. “Once you understand that they are receiving these funds, you can kind of go straight from there down to how much and who has received it at that level.”

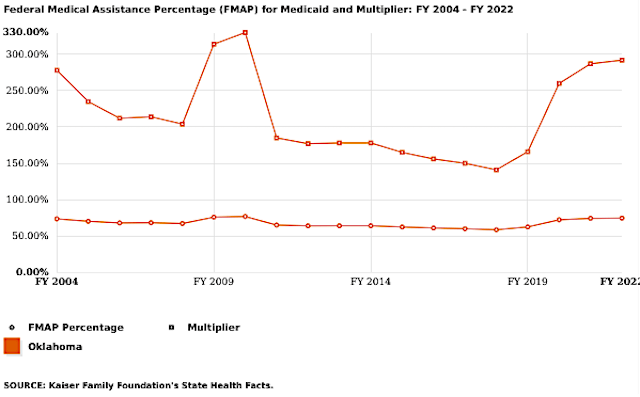

The team learned that in 2019, Indiana received $679 million in extra Medicaid payments for nursing homes, more than any other state. These extra payments, known as supplemental Medicaid funds, are meant for nursing homes owned by local governments. In Indiana’s case, that government entity was the county hospitals.

A decade earlier, Evans had been part of a team at IndyStar that reported on a scheme where a local county hospital was buying nursing homes to qualify for the supplemental Medicaid funds. He did the story and moved on.

“The first step is to understand whether or not your state receives these types of funds. Once you understand that they are receiving these funds, you can kind of go straight from there down to how much and who has received it at that level.”

Emily Hopkins

The team found that since then, county-owned nursing homes had become the norm rather than the exception. By 2019, nearly two dozen county hospitals had bought up 93% of Indiana’s 534 nursing homes. A regulatory loophole allows the hospitals to spend the money on non-nursing home expenses, such as new hospital construction. Because Medicaid officials don’t track how the money is spent, the amount of money the hospitals divert remains a secret.

No one at the state or federal level knew how much Medicaid money had been siphoned away.

The reporters asked the 22 county hospitals, which are public entities subject to records requests, how much money they had diverted from nursing homes. Only seven responded, acknowledging they had redirected between 66% and 70% of the supplemental Medicaid funds to the hospitals. The reporters determined that county hospitals had diverted at least $1 billion of the $4.5 billion in enhanced Medicaid funding they had received since 2003. They estimated that the true total could be as much as $3 billion.

The reporters also wanted to know how supplemental Medicaid funds compared with the regular Medicaid rate and how much money each Indiana nursing home received. They asked the state health department, which pointed them to an accounting firm that had done the calculations for the state.

In Indiana, Medicaid pays nursing homes an average of $207.91 a day for each patient. But nursing homes owned by county hospitals get another $120.38, or 58% more, the reporters learned. They also learned how much additional Medicaid money each nursing home was generating. To get historic data, they filed a public records request with the state.

Tip: Understand the structure of your local hospitals. Are they public, nonprofit or for-profit? Find out what financial documents they have to file with local or state authorities. And check free sites like EMMA to find their financial reports and public debt.

But the officials at the county hospitals wouldn’t say how they spent the money. County hospitals are funded by a variety of taxpayer funds, such as Medicaid, Medicare and sometimes local taxes. As public agencies, they must make public records available, but officials told the IndyStar that the information the reporters requested was a “trade secret” and exempt from public records laws. They denied their requests, which the IndyStar is appealing.

“County hospitals are public entities but they operate and act a lot more like their private counterparts,” says Hopkins. “They’re not used to being held accountable or being transparent in the way that other agencies are. So I think they were very taken aback when they started to receive these [public records] requests.”

In Indiana, county hospitals have to file annual financial reports with the state. That helped the IndyStar team find out how much the county hospitals had come to rely on nursing home funding. For at least two hospitals, the nursing homes made up 40% of the money the hospitals brought in.

Unraveling a complicated structure

The fraud tip that Cook had received in 2019 helped the investigative team learn that even though many Indiana nursing homes were owned by county hospitals, a private company oversaw them.

The investigative team then asked the county hospitals for copies of their contracts with the nursing homes. Only a few provided them, however.

Cook, Evans and Hopkins learned that county hospitals set up contracts that brought nursing homes under their names. The state allowed the county hospitals to buy nursing homes outside their counties, too. Meanwhile, the private nursing homes continued to own the nursing homes’ buildings and managed their day-to-day operations.

The reporters also learned that the hospitals gave almost all administrative control over the nursing homes to the private companies. For instance, county hospitals had no say on nursing home staffing decisions.

“One of the things that we were trying to drill into the readers’ minds was that these county hospitals really don’t have much to do with the nursing homes, except financially,” says Hopkins. “So you have these CEOs who technically, you know, should be responsible for this vast network of health facilities that are under their portfolio. But they kind of only focus on the hospital.”

CEO salaries

County hospitals refused to disclose their CEO salaries. And the reporters could not retrieve the data from IRS Form 990s because public hospitals don’t file them. That’s unlike nonprofit hospitals, which are tax exempt, and must file Form 990 annually to provide information about their revenue, expenses and executive compensation.

But the IndyStar team realized that many hospital have foundations, which are nonprofits and have to file an IRS form 990 annually. Hospital foundations raise money for projects and services. The journalists found information about county hospital CEO compensation in a fraction of those tax filings.

“So we were really working with breadcrumbs,” says Hopkins. “But fortunately for us, from a storytelling standpoint, there was a really big breadcrumb in that we found that one hospital CEO for a small, rural county hospital was being compensated a multimillion-dollar package and there was no explanation for that.”

He was making more than the CEO of Indiana University Health, the largest nonprofit hospital in Indiana, says Hopkins.

“Just don’t take no for an answer. Because when we’re told, ‘Nope, you can’t get CEO compensation data,’ then you just have to say, ‘Well, how else can we get it?”

Tony Cook

The journalists consulted data from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics to find out how much a CEO for a local government-owned hospital earns in a year. The national average: a salary in the low six figures. That’s much lower than the seven-figure salaries of some county hospital CEOs in Indiana.

Cook says that journalists sometimes have to look in multiple places to track down the information.

“Just don’t take no for an answer,” says Cook. “Because when we’re told, ‘Nope, you can’t get CEO compensation data,’ then you just have to say, ‘Well, how else can we get it?'”

Calculating nursing home ratings

To find out how Indiana nursing homes ranked nationally, the investigative team didn’t rely on state or federal level star ratings, which are usually touted by the nursing homes. Instead, they zeroed in on staffing to create their own ranking system based on government data.

The journalists explained their methodology as part of their first story in March 2020.They used data on nursing home staffing published by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The federal agency publishes a variety of data on staffing levels. The team used adjusted hours, which represent the reported hours adjusted for how sick the residents are. They compared the data across states and ranked Indiana 48th.

“These are super vulnerable people who don’t have a lot of people advocating for them, so I would say dig into that data and find the worst nursing homes and write about them.”

Emily Hopkins

If you want to know about the quality of local nursing homes, focus on their staffing levels, advises Hopkins.

“Nursing home academic researchers as well as the federal government, which produces the stats, say staffing is the most important thing,” Hopkins says.

Hopkins adds that aside from Medicaid funding, there are lots of stories about nursing home quality at the local and state level. All you have to do is look.

“It could be one really bad facility that stands out against the rest,” Hopkins says. “It could be a chain. There’s a story there and these are super vulnerable people who don’t have a lot of people advocating for them, so I would say dig into that data and find the worst nursing homes and write about them.”

Finding consumer voices: lawsuits and inspection reports

To find people who had been impacted by low staffing levels at Indiana nursing homes, the reporters began scouring civil lawsuits and nursing home inspection reports, also known as survey reports.

“We found the full picture exists in those wrongful death claims and the survey reports, where you read about the actual suffering of people rather than this calculated number or rating,” says Hopkins.

The three journalists looked for lawsuits but didn’t find as many as they thought they would. The ones they found were filed against anonymous nursing homes.

They called the plaintiffs’ attorneys and learned that malpractice claims, including wrongful death claims, are first filed with the Indiana Department of Insurance. The cases then goes in front of a medical review panel before they become a lawsuit. Until there’s a judgement from the medical review panel, the nursing home cannot be named, they learned.

Tip: Look for nursing home inspection reports, both at the state and federal level. “We found the full picture exists in those wrongful death claims and the survey reports, where you read about the actual suffering of people rather than this calculated number or rating,” says Hopkins.

“So we learned that we had to look for these claims through the Department of Insurance, not through the court system,” says Cook.

The team also scoured inspection reports available at the state and federal level. While different agencies are in charge of inspections at the state level, federal inspection reports are available on Medicare.gov’s Care Compare website.

Cook recommends journalists look at reports at both levels.

“Sometimes, they look kind of different because the state will include nursing homes’ responses but the feds won’t,” Cook says.

After their first story in March, they put out a call for people who wanted to share their experiences with Indiana nursing homes.

“I think at this point, we’ve probably received more than 100 responses to that call out,” says Cook.

Conducting a team project during a pandemic

The IndyStar investigative team started the project in person in 2019. But as their first story was published in March last year, COVID-19 had started to spread in the United States and they had to stay home.

For the remainder of the year, the trio worked remotely via Google Docs and Google Sheets. They held numerous conference calls via Microsoft Teams.

“There would be times where we would have a Google Doc up and we would all be on audio on Teams and just working through it and we would just leave the audio up for hours and hours so they would hear me yelling at my kids in the background,” Cook recalls. “So it was like we were all in a virtual conference room in a way, but with all these other distractions happening at the same time.”

The three shared responsibilities and picked up the load when each had to go on furlough for three to six weeks at a time. Their editor, Berta, took a buyout last year. He edited all but one story in the series.

“I got therapy at the end of year and it helped a lot. And I don’t think that any of us going through what we’re going through right now should be scared or ashamed of doing that.”

Emily Hopkins

“It was a challenge, especially on a big project like this, because of the pushback that you get from the people who don’t want you to report out these stories,” Cook says. “It’s very lonely work in a way. And to not be able to have the camaraderie of at least being with Tim and Emily every day in person and with our editor in person makes it more challenging to do this kind of work without that kind of moral and social support. Everyone’s schedule is thrown into flux because of virtual schooling with the kids or other things.”

The trio is lucky to get along well, they say. But the pandemic, the isolation and witnessing nursing home deaths took a heavy mental toll.

“I got therapy at the end of year and it helped a lot,” says Hopkins. “And I don’t think that any of us going through what we’re going through right now should be scared or ashamed of doing that.”

Additional resources

Clipped from: