MM Curator summary

The article below has been highlighted and summarized by our research team. It is provided here for member convenience as part of our Curator service.

[MM Curator Summary]: The Medicaid wind-down will also have effects on other benefit programs like SNAP.

Expansions to social safety net programs during Covid-19 have been essential for low-income Americans hit hard by the pandemic. But the stabilizing impact of these expansions will be at risk when the federal Covid-19 Public Health Emergency, which was initially declared on January 31, 2020, comes to an end, possibly by Jan. 11, 2023.

Ending the public health emergency will end expansions to Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the nation’s flagship programs that provide individuals or households with low incomes health insurance and combat hunger, respectively.

Households rarely experience food insecurity, poverty, or poor health in isolation. Instead, they are linked in a cycle in which high health care costs strain household budgets and lead to food insecurity while, at the same time, food insecurity leads to stress and poor nutrition, which results in poor health.

advertisement

Given significant gaps between wages and costs of living for families with low incomes, households generally participate in multiple federal assistance programs to make ends meet. In 2017, 89% of children receiving SNAP support also received support from Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). During Covid-19, both programs experienced dramatic increases in enrollment.

When the public health emergency ends, many individuals and families will experience the cumulative impact of losing access to both Medicaid and SNAP or losing access to Medicaid and having SNAP benefits reduced. Health care organizations must take an active role in supporting patients navigating the systems necessary for them to access health services and achieve food security.

advertisement

Double loss of Medicaid coverage and SNAP benefits

The end of the PHE and the program expansions attached to the declaration will significantly affect millions of Americans who continue to struggle to access medical care and afford food.

Much has been written about the “unwinding” of Medicaid and SNAP. In brief, when the public health emergency ends, program benefits and access will be affected in myriad ways:

Medicaid: Access will be restricted as states will discontinue continuous coverage — under which Medicaid agencies have been prohibited from disenrolling participants unless they request that, move out of state, or die — and will return to annual reviews to determine Medicaid eligibility. Enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP increased by 12 million between March 2020 and July 2021, an increase that was largely attributable to automatic renewals keeping people covered, rather to than new enrollees. An estimated 5 to 14 million people could lose Medicaid coverage, depending on how states make their Medicaid redeterminations.

SNAP: Benefit levels will be reduced following the expiration of SNAP’s Emergency Allotments, which entitled participants to the maximum allowable benefit for their household size. On average, participants will lose an estimated $82 per month. Access to SNAP will also be restricted as three-month time limits are reinstated for able-bodied adults without dependents, which has been shown to reduce enrollment among eligible adults, and exemptions for college students come to an end, which had simplified the eligibility requirements for college students and enabled an estimated 3 million additional students with low incomes to qualify for SNAP.

The loss of Medicaid will affect access to other food assistance programs, further increasing food insecurity. Medicaid coverage confers automatic income eligibility for free school meals (also known as direct certification) and for WIC, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children (also known as adjunctive eligibility). As more than three-quarters of WIC participants rely on adjunctive eligibility, ending continuous coverage could result in a loss of WIC coverage.

Linkages between food insecurity and access to health care in the pandemic

Interviews with representatives of Medicaid managed care organizations indicate that the pandemic highlighted the “magnitude of unmet social needs” facing their patient populations — needs that existed long before the onset of Covid-19. Of all the social determinants of health, food security, they note, was the most urgent concern among those covered by Medicaid at the onset of the pandemic.

Individuals who experienced food insecurity before the pandemic were more likely to forgo health care, a trend that has continued during the pandemic, when overall rates of forgone care have been an ongoing concern. One study, for example, found that adults who reported food insecurity were more likely to forgo medical care, while another study found that delaying pediatrician visits due to Covid-19 was higher in households where children did not have enough to eat.

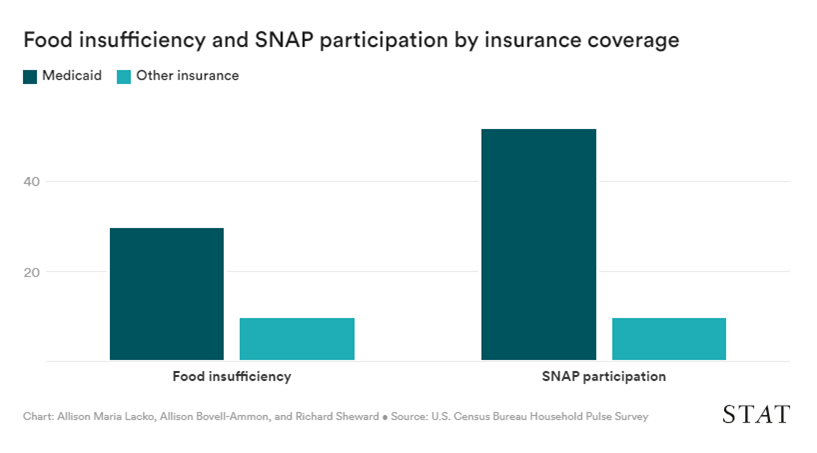

Evidence of the co-occurrence of hardship continues into 2022 for households with low incomes. Using data from the Census Household Pulse Survey in July and August of 2022, we found that 30% of respondents covered by Medicaid reported sometimes or often not having enough to eat — formally known as food insufficiency — and that 52% reported using SNAP (see the chart below). These results are expected, as people covered by Medicaid have low incomes and are more likely to participate in SNAP. What these data emphasize is that many individuals stand to be harmed by the simultaneous rollback of benefits from both programs.

Given the interconnectedness of health and food security and the inevitable rollback of expansions to Medicaid and SNAP when the public health emergency expires, actions by health care organizations, advocates, agencies, and policymakers are vitally necessary.

Actions for health care organizations

- Increasing the capacity for addressing health-related social needs is the place to start. For example, heath care organizations should maintain external active partnerships with community organizations to address health-related social needs. This is especially important for quickly adapting to emergencies like Covid-19. Donald Berwick, the former administrator of the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, has suggested that health care organizations invest in teams dedicated to addressing health-related social needs, including food security.

- Health care systems collect and store rich health data. Through actions such as integrating food insecurity screening questions and referrals into their electronic health record systems and health outcomes tracking, health care systems can generate implementation science studies and case studies that provide evidence of workflows that strengthen enrollment in social safety net programs.

Actions for community-based organizations and state agencies

- Medicaid agencies can adopt several best practices, including simplifying the process for enrollees, reducing the burden on frontline staff, conducting outreach to update contact information, and facilitating transitions to other coverage.

- SNAP state agencies should request waivers of the three-month time limit for SNAP able-bodied adults without dependents as soon as 60 days’ notice is given of the end of the public health emergency, because the U.S. Department of Agriculture recommends submitting a request for waivers 60 days before the implementation date.

- Medicaid agencies should adopt the CMS state option to automatically renew Medicaid coverage for participants under 65 who receive SNAP. Since nearly all SNAP participants qualify for Medicaid, this will reduce administrative burdens for state and local agencies and will prevent participants from temporarily losing coverage during the redetermination process.

- The 12 states that have not done so should expand Medicaid. Increases in Medicaid enrollment after Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act were associated with reduced food insecurity in California.

- Community-based organizations and state agencies should have resources ready for those households who have improved their income and no longer qualify for SNAP or Medicaid but are still struggling with food insecurity.

First Opinion newsletter: If you enjoy reading opinion and perspective essays, get a roundup of each week’s First Opinions delivered to your inbox every Sunday. Sign up here.

Actions for policymakers

There is much that policymakers can do to help reduce food insecurity after the public health emergency is lifted. They can streamline access to Medicaid and SNAP; increase SNAP benefits so they cover the cost of a healthy diet; eliminate the SNAP three-month time limit for able-bodied adults without dependents at the federal level; improve access to SNAP by low-income college students who are otherwise ineligible for benefits; and support SNAP administration through automatic response during disasters and increased funding.

As the public health emergency comes to an end, the U.S. must be ready to ensure that it does not jeopardize the health and food needs of households across the country. Urgent action by health care systems, community organizations, and all levels of government will be necessary to stabilize health and food security among those at greatest risk. While vaccines and treatments lessen the life-altering threat of Covid-19, it is important not to lose sight of the imminent danger to health posed by the expiration of effective expansions of Medicaid and SNAP.

Allison Maria Lacko is a nutrition and policy researcher at the Food Research & Action Center in Washington, D.C. Allison Bovell-Ammon is the director of policy and communications for Children’s HealthWatch at Boston Medical Center, where Richard Sheward is the director of system implementation strategies.

Clipped from: https://www.statnews.com/2022/10/18/ensuring-food-security-and-health-beyond-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency/